Why we find SaaS compelling

One of the themes we have become increasingly interested in is SaaS (Software as a Service). The old model of software was predicated on selling it once, like any other product you might buy -- a fishing rod, a cup or a new set of dinnerware. Companies would spend years developing a new piece of software, spending millions in the process, and then eventually sell & market it which would provide a large influx of cash. It was a cyclical business: a new version of Photoshop might generate a lot of revenue for Adobe but the years spent developing the next version would be fairly lean. This is not remarkable. It is how most consumables work. The unique thing with software is that once it has been produced the cost of production becomes almost zero. A car company still requires the raw materials to manufacture a new car. A software company essentially just needs to copy and paste the software itself: it is infinitely replicable with very little material cost.

So, then, the idea of selling software as a one-off makes little sense when you consider there is no inherent cost of reproduction. There is no iron or rubber or glass. Yet this served as the dominant software model for many years. This was largely due to the high cost of storage, relatively slower internet speeds and the lack of “the cloud”. The cloud, in many ways, made SaaS possible -- the cloud takes advantage of cheap, mass storage solutions and fast internet, as well as similar peer-to-peer architecture. Once the cloud made SaaS feasible, companies with forward-thinking management quickly shifted to the model -- the paramount example is probably Adobe, who transitioned in 2012 to a fully SaaS model: users would pay monthly for access to some, or all, of Adobe’s creative suite. The fee would be nominal -- $50 for the full suite rather than hundreds of dollars for the one-off product. It was like having a subscription to Netflix or the gym -- small recurring nominal fees rather than a large one-off fee.

Rationally small incremental payments should be treated the same as one large payment. A SaaS subscription of $50 per month for a year is precisely the same as a one-off fee of $600 per year. This doesn’t consider mental accounting -- mentally we treat $50 a lot differently to $600. “Big ticket” purchases occupy a different part of our brain compared to a “nominal” amount. Soman and Gourville presciently wrote as much in 2002 in the Harvard Business Review:

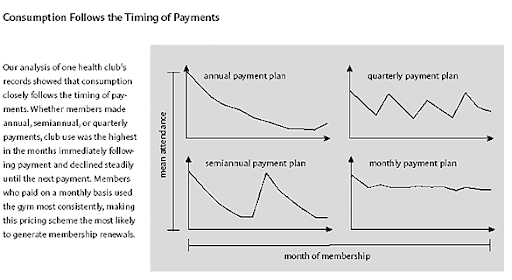

Consider this example. Two friends, Mary and Bill, join the local health club and commit to one-year memberships. Bill decides on an annual payment plan—$600 at the time he signs up. Mary decides on a monthly payment plan—$50 a month. Who is more likely to work out on a regular basis? And who is more likely to renew the membership the following year?

Almost any theory of rational choice would say they are equally likely. After all, they’re paying the same amount for the same benefits. But our research shows that Mary is much more likely to exercise at the club than her friend. Bill will feel the need to get his money’s worth early in his membership, but that drive will lessen as the pain of his $600 payment fades into the past. Mary, on the other hand, will be steadily reminded of the cost of her membership because she makes payments every month. She will feel the need to get her money’s worth throughout the year and will work out more regularly. Those regular workouts will lead to an extremely important result from the health club’s point of view: Mary will be far more likely to renew her membership when the year is over.

Source: Harvard Business Review

We think this captures the unique power of SaaS. Behind every good business is a strong psychological rationale. There is a number of practical reasons why SaaS works, as well -- infrastructure and software can be updated rapidly, rather than a two-year development cycle; the product is always the newest possible product.

We have acted accordingly and added SaaS-based companies we consider to offer compelling value. We recently added both Squarespace and Avid Technology to the Elevation Global Shares Fund. Squarespace is the market leader in website hosting & design service: it has a growing base of subscribers and effortless integration of commerce and scheduling services. Squarespace has +3.9 million subscribers who pay an average of $193 per subscription. This, we think, is a succinct illustration of the power of SaaS economics (we use Squarespace ourselves, for this very website).

Avid Technology (Avid) is the leader in software for “big budget” film and music editing. Four in five Hollywood productions are made using Avid’s Media Composer software. The majority of major label music releases are made with ProTools, their music editing offering. The amount of investment being made in both fields of high budget content by Disney, Netflix, Amazon, Discovery and so on necessitates more use of Avid’s industry-essential software. Avid was hesitant to move to SaaS at first; new management has spurred the move to SaaS since 2017 and the results look incredibly promising. Look out for our forthcoming research on Avid and Squarespace.